A Wednesday night post for “Mom & Dad Monday”

Continue readingJust Another Manic Monday. . .

The Tale of the Bloody Eye: this week’s Adventures in Caregiving

Continue readingPlease Don’t Tell me it’s Sad

A more critical look at what’s *really* sad about dementia.

Continue readingMom & Dad, Inc. (Guest Blog by Nancy May)

I’ve always joked with friends about how my parents have been preparing me for their death since I was five. In fact, as a little girl, my mom and aunt would playact that Mom had fallen ill and couldn’t get up. While Mom lay on the living room floor, my aunt would yell “Help, Help! Nancy call the doctor: Mom needs help!”

Using my trusty red plastic dialup telephone strategically placed on the coffee table by where Mom was lying, I’d dial 911 and tell the make-believe doctor to come quickly as Mom was dead on the floor and needed help, NOW! My aunt would run to the front door and clang the long brass tubes that were our doorbell, alerting me that the doctor had magically arrived at our front door for me to let in so he could revive Mom. Of course, I’d get praised for a great job while they went off to laugh, relax, and share a smoke together.

As I got older, I was told where critical documents were kept in file cabinets; names, phone numbers, business cards, what local banks we used, even personal introductions to the family attorney, accountant, financial advisor – and what was in each account. I got pop quizzes on all of this. At the time I thought this was a bit overkill. Looking back, I understand how life’s tragedies, such as the passing of their parents, and later my sister at age four made it imperative to them that I be able to carry the torch, on my own, if necessary. As the eldest daughter, I was prepared at an early age to become the caregiver they now need.

Over the last nine years my sister and I have gone through a steep learning curve. We’ve learned that nothing can totally prepare you for what’s needed to physically, mentally, or financially to take over the care of a parent or loved one.

I first wrapped my head, heart, and hands around this idea (which later became a substantial and complex project) after my husband drew my attention to small changes in Mom’s conversations. Later, after utilities were cut off for failure to pay bills – which was always Mom’s responsibility, while Dad ran the business – reality and the need for action kicked in fast.

With their first move into Assisted Living (this move was their choice as they both said “we don’t want to be a burden on you kids), Dad called me in a panic five days from their move-in date. He’d been blindsided by Mom, thinking they had two more months to go. I jumped into the deep end, learned to swim, and have been doing laps ever since. Doing the backstroking has become much easier with practice.

We who care for our parents have learned to manage in our own way – often only with subtle differences. My approach is to take charge of ‘Mom & Dad, Inc.’, complete with a team of caregivers who are with them 24/7. Doing this work long-distance isn’t easy, and Mom, Dad, and our amazing ladies are always on my mind, and in my heart. There have been some bumps and bruises along the way for all of us, but I managed to acquire some life and business lessons along the way.

I’ve shared my journey with friends, family, and strangers. Having heard my story and faced similar situations, many have asked themselves: “What would Nancy do?” As an entrepreneur I’ve learned much from walking alongside Dad at his factory and getting to know his employees, customers, and industry colleagues. Without knowing it, he and Mom have been the cartographers for my own exploration and learning. Watching them flourish (or sometimes deteriorate, but they always spring back) from my decisions, I manage Mom & Dad Inc. like a well-oiled enterprise: overseeing their welfare; hiring and firing various ‘’professionals;’’ identifying vulnerabilities; and removing the weakest links quickly, in medical, legal, financial, daily care, and even supply chain services. All the while, I’m keeping a focus that this is personal for them, as well as for my sister and me.

This has become my nature. Running a business and advising large company leaders, CEOs, and boards is a walk in the park compared to managing the business of being a caregiver. Working this way has helped me keep everything in perspective without becoming an emotional wreck – although I’ve had those moments too.

My commitment to doing what’s good, healthy, and right for Mom and Dad has become an obsession. Like the service that I deliver to my corporate clients, I give the best guidance and support to others who become overwhelmed by what it takes to be a caregiver: courage, character, and confidence to keep your head high when the day presents dark clouds and fears creep into your mind.

This is a tough road for anyone. Society shuns the elder caregiver, not knowing what to do with and for us. It’s why I’ve started sharing options, opportunities, and positive outcomes that have helped others in a new Facebook group called Eldercare Success!

Through this group, we caregivers come together, confidentially, to help, support and take some of the emotional, physical, and financial fear out of our own hearts. That’s the mission for me and others in our Eldercare Success group. We’ve grown over these few short months, now that word has spread that this is a safe and trusted space. In fact, we just launched, Eldercare Success UK. There are no borders when it comes to the challenges we face as caregivers. I expect that there will be many more Eldercare Success Groups in the near future.

If you, a friend, or family member needs a safe, trusted, empathetic and valued place to ask for and give support to others, come on over and join us. You’ll find joy in the little things, and a way to relieve stress and frustrations as we work to provide the best for those we love. As I say in the group: “Together We Are Stronger!”

Walking at your side!

About Nancy May:

Nancy May, CEO, The BoardBench Companies, and noted in Forbes as one America’s governance experts, knows the ins and outs of challenging board environments. Nancy hosts the Boardroom’s Best podcast, which was recognized among the top 25 business podcasts to listen to in 2018. She is a regularly featured contributor to the CEO Forum Magazine, and is a frequent guest speaker on corporate boards, governance trends, and how candidates can “crack the code” that gets you to a seat at the table. She has been a guest lecturer and presenter for numerous national and international business and professional organizations and universities.

Ms. May has been recognized by clients for her innate ability to quickly identify key action points and resolve complicated boardroom and business challenges impacting corporate governance and performance. Her skill and insight into many different industry environments comes from her long-term, diverse experience with many companies from rapid-paced start ups and IPOs, to broad complex corporations and institution.

She also freely applies her skills to the needs of others like herself. In addition to her work in the boardroom, she has been the primary guardian and caregiver for her elderly parents for more than 10 years. Openly sharing some of the most challenging issues that caregivers confront, she has become a “go to” for many executives and friends who find themselves physically, emotionally, and professionally overwhelmed. Nancy’s strength and advice, has been a grounding force for many, includng that of her own family and an ever-expanding group of caregivers.

Parenting the Parents, Part XIV. Thyroid Nodules and Escape Acts.

Time for some positive energy for a couple of reasons: 1) Mom’s thyroid ultrasound was Wednesday. She has a 3cm nodule (medical code for a tumor, and 3cm isn’t a tiny one) that is defined as “complex.” While that doesn’t necessarily mean cancer, it could. I should be getting a call from the doctor’s office today or tomorrow to schedule a needle biopsy. 2) On Tuesday night, sometime around 3 a.m., for the first time, dad wandered out of the house.

Not the worst thing. . . maybe

Let me take these one at a time. First, mom’s thyroid: I suspected things might begin to unfold like this when the doctor called me last Tuesday evening while we were on vacation, filling me in on what he was seeing from the CT scan mom had had the previous Friday, and letting me know that the thyroid ultrasound was in order. If there were nothing concerning in that CT scan, I’m pretty sure a follow up call might not have come at all, or wouldn’t have been quite so soon. So, when the doctor called last night, on the same day as the ultrasound, I was certain it wasn’t just to convey an all-clear.

Now, I do realize that of all the vast array of cancer possibilities that exist, thyroid cancer isn’t the worst. The majority of thyroid cancers are highly treatable and, overall, have a 98% 5-year survival rate. I also know this survival rate can be quite different depending upon the specific type of cancer, stage, and the age of the patient. No matter what, all we can do is take this one step at a time. I decided not to tell mom about it last night so she wouldn’t stress out and keep herself awake. (I’ll tell her as soon as I hear from the doctor’s office and have the biopsy appointment set up. I did prepare her for this possibility after the ultrasound, so hopefully it won’t come as a shock).

Secret Houdini

As for dad and his . . . expedition, Mom slept right through it, and only discovered it when, in the morning, she looked out the front window to see if the newspaper was on the stoop and saw his walker, sitting on the sidewalk, dripping from the rain and mist that had persisted all night. He had come back in and by then was snoozing in bed, but immediate action was clearly in order to prevent another such incident, possibly with a much worse outcome. When mom asked him why the walker was outside, he told her, in full detail, how he’d gone out and exactly where he’d gone (farther than he’s probably walked cumulatively over the past month). The one thing he couldn’t tell her: why he decided that he simply had to go for a walk, outside, in the cold drizzle, at 3 a.m. I think he was bored.

How someone with very limited agility managed to Houdini himself – and his walker – out the door, down the (thankfully only 2) steps to the sidewalk, then on a downhill trek with an uphill return that spanned about 400 yards round trip, unaided, is beyond me. I forgot to ask him what he had on his feet!

The Solution, for Now

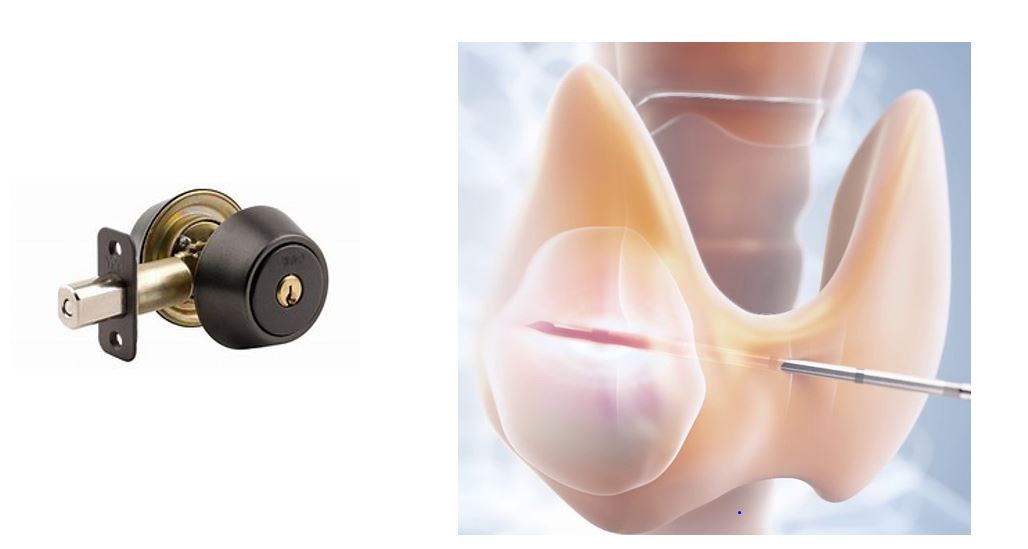

There are two exit doors on their main floor (and a bank of sliders in the walk-out basement, but we keep the basement door locked with a two-sided, keyed lock so dad doesn’t accidentally open it and fall, thinking it’s a door to somewhere else). The front door has a deadbolt with a flip lock on the inside, and the garage door has a regular knob-lock, like one you’d find on most bedroom or bathroom doors, but with a keyed entry on the outside. I thought at first that we’d change the front door deadbolt to one that’s keyed on both sides, along with switching out the garage door with one similar to the one on the basement door. Mom could wear the keys on her fall-alert pendant.

Upon further thought (and a conversation with the lockset guy at Home Depot), we concluded that having 2 keyed locks could be a hazard if there were ever a fire and mom wasn’t able to find the keys (even though, in theory, she’d be wearing them; if she ever took the pendant off and forgot to put it back on, the panic of an emergency would surely obliterate her ability to think clearly about where she put the pendant and the keys). So as at stop-gap solution, we bought 2 magnetically activated, stick-up door alarms that go off when the door is opened and the magnetic field between the 2 contacts is broken.

Disarm Alarm

We “installed” the alarms on both doors last night, with the intention of going out today to pick up the double-keyed deadbolt for the front door. We tested the alarms, showed mom how they worked, made sure they were set, and said our goodnights. At 8:50 this morning, my phone rang. It was mom. I picked up with my usual upbeat, “Hey! What’s up?” It took her a good 20 seconds to communicate that she didn’t know how to turn off the door alarm, and she was not happy. Oh boy. It wasn’t shrieking in the background as we talked, so obviously she at least remembered that you just need to close the door to make it stop. I couldn’t initially determine why simply closing the door was so distasteful, but when I offered that as my first solution to the problem, it riled her up even more than she already had been. Oops. I realized later it was because she wanted to leave it open as she stepped outside and down the stairs to pick up the newspaper.

Her frustration built as she sputtered through what she thought she was supposed to do to disarm the device, none of which was making a shred of sense to me. I thought she was standing in front of the alarm and trying to figure out how to disable it. It took another minute or two of attempting, and failing, to guide her through how to turn off the switch for me to figure out that was what was happening:

“Are you at the actual door looking at the alarm, or reading off the instructions?”

“Both, but I’m looking at the paper.”

“OK. Put down the paper and just look at the alarm itself and I’ll tell you how to shut it off.”

After another 2 minutes of me trying to walk her through the process, step-by-step, it was clear that absolutely nothing I was saying to her was landing – the circuits were shorting. I told her I’d be down in a couple of minutes.

She was in rare form when I got there – upset and mean-spirited, saying she didn’t care if he just went out the door and never came back. I let that bounce off and said I understood – which took a lot of energy – then showed her (again) how to slide the cover off the alarm (even though she thought we didn’t show her last night), how to move the switch to turn it off, or to switch it to “beep” mode (so it would just beep once if someone opened it). Hugging her, I apologized (I felt for her in her confusion, even if her anger was really getting to me this time), but her dark mood relented only slightly. I told her we’d be back later after we picked up the new deadbolt, and beat a hasty retreat back home to finish my coffee and to steam quietly in my own annoyance.

The Solution, Part II

Tim had taken his niece to the airport, and when he returned, much to my delight, he announced that he’d bought the deadbolt on the way home. After he finished his coffee and got in a round of post-primer sanding on the trim in the hallway-under-renovation, we rolled back down the hill. Hannah, their caregiver, was there by then, and dad was up and sitting at the kitchen table, finishing his breakfast. Mom was nowhere to be found (Tim thinks she was hiding in the bedroom, feeling a little sheepish over her earlier behavior – he may be right).

By the time we completed the installation of the new deadbolt, she’d made an appearance, though with only slight mood improvements. Tim and I left to have copies of the key made at the hardware store and picked up a lanyard for one copy that would stay in the door during the day and be worn with her fall button at night. I had one of the copies made with a specialty head design in the shape of a little house, with the word “Home” on it, for her regular keychain, to make it easy to differentiate between that one and the one for the garage. When we got back, I tested both of her keys to be sure they worked, and she seemed to get a little lift from the “home” key – small victories – though we were still far from “normal.”

I’m considering whether I need to go over there every night to set the alarm on the garage door for her, then go back every morning to turn it off. For dad to get out of the garage and into the world would take a lot more (relative) Houdini-ing than slipping out the front door, so for now I’m content to see how it goes over the next day or so, and look into an alarm mat!

Parenting the Parents – Part XII. The Cataract Chronicles, continued.

The Friday before mom’s second cataract surgery, as I mentioned in my post a couple of weeks ago, was her first appointment with the geriatric psychiatrist, Dr. M. We came away from that appointment with a prescription for a medication to treat her depression, with him telling mom that any side effects were rare and, if any appeared, typically very mild, tending toward those of the gastrointestinal variety. He recommended that she take it in the morning with food to avoid any of those potential side effects. I swung by the pharmacy first thing on Saturday morning to pick up the prescription, and since by now we were back on the 3 eyedrop-a-day regimen for the second pre-surgical eye (while still administering 2 a-day for the first eye), I dropped it off when I delivered the first round of drops for the day.

There were 2 dosages of the depression medication: a lower dose to start for the first week, then a higher dose she was to take for another week and ½ before her follow up appointment with Dr. M. I put the higher dosage bottle away in the cabinet, leaving the lower dosage one on the kitchen counter where she would see it in the morning when she made her breakfast. I left all the standard literature that comes with any new prescription off to the side on the kitchen table. I came back in the early afternoon for round 2 of the daily eyedrops to find my mother somewhere well-beyond agitated, bordering on the accusatory:

“I’m not taking those new pills.”

Instantly I knew what had happened.

“I read those papers and it said there could be eye problems so I called Dr. M’s office and told him I’m not going to take them.” She didn’t want to risk messing up the surgery.

I started to remind her that Dr. M had said that the side effects were rare and mild, but thought better of trying to talk her into it at this stage given her frenzied state of mind. She continued, attempting to convey her concerns, her frustration building , unable to extract and articulate the thoughts in her head. I quickly put it all together based on the sentence fragments she was hurling at me. Her eye doctor didn’t know about this new medication because she hadn’t been on it when they last reviewed her medication list. Then she wasn’t sure *who* she’d called, causing her more frustration, so I looked at the call log on the phone. Turned out she’d called the eye surgery center. I told her they weren’t open on the weekends so they wouldn’t be getting back to her until Monday morning, but also conveyed not to worry about it – if she wasn’t comfortable taking it yet, then she shouldn’t take it. We’d wait to hear from the surgical center or the doctor on Monday to be sure it was OK, and if it was, she could just start it on Tuesday, since she had to fast Monday morning before the surgery.

Monday morning the surgical center called back and told her the medication wouldn’t interfere with her surgery. I did the drops, later than normal, just before we left for the surgery, which, this time, was scheduled for noon. All went well, and, because she now knew what to expect, though I offered to stay over again this time, she was comfortable with me spending that night in my own bed. I reminded her though, that if anything was even a little bit off, she should just call me.

I arrived the next morning around 9:15 to help her remove her patch and dressings and to be sure she ate something and took her first dose of her new medication. Her appointment was at 10:15, so we were planning to leave a little after 9:30, so I was surprised to find the place eerily quiet. I called out. No answer. I wondered if she’d overslept.

I went to their room to find her sitting in the chair next to her dresser, in quiet tears. She seemed shaky and weak. Panic rose. She said she was feeling dizzy and strange and that she didn’t think she’d be able to go to the appointment. I felt her head for fever as I ran through the list of post-op complication warning signs I’d since memorized: bleeding through the dressings (no); fever (no – though she was a little sweaty); chills (she said no); nausea (no); vomiting (no); pain at the surgical site (it felt like the other eye had, so no). I asked her if she’d eaten anything (no), so I went out to the kitchen, peeled her a clementine, poured a fresh glass of cold water, and brought them in to her.

It was imperative that we see the doctor that day for the post-op follow up, but I told her not to worry – that I would call to change the time to later. While she ate the clementine, I called the doctor and left word on his assistant’s voicemail with what was happening and asking if we could bump the appointment to later.

After a few minutes, mom seemed marginally better. I made her some toast. Hannah had arrived so she helped her finish getting dressed. They came out to the kitchen and I went back to get my phone off her dresser, distracted for a minute by a reminder that had popped up on my screen. I came back into the kitchen to butter the toast. By now she was sitting in her spot at the table, so I washed my hands in preparation for removing her patch and dressings and doling out another dose of eyedrops. The eye looked red, as the other one had the morning after surgery, but nothing alarming. I decided to wait on the eyedrops until after she’d finished her toast.

As I went back over toward the sink to grab a napkin for her, I saw the bottle with the new medication on the counter, so took one out and brought it over to her to take now that she was eating something a little more solid. As I laid it on the table next to her plate, she said, “Oh, I took that already.” (What?!?)

“You did? When? Like before I got here this morning, or just in the past few minutes?” (Could she have taken it in the time it took me to get my phone?)

She thought for a moment. “Before you got here. I was up early and walking around and I saw it so I took it.”

“Did you eat anything when you took it?”

“No.”

“I think that’s why you were feeling so dizzy and strange! Dr. M said you should take these with food or they might make you feel funny. How are you feeling now that you have some food in you?”

“Better.”

My phone rang. It was the doctor’s assistant. I explained what I thought had happened and that I thought we may still be able to make it but we might be a few minutes late. She said not to worry and did some re-arranging of the schedule, working us in after 1:00 that afternoon instead. Perfect.

Mom finished her toast, now on the upswing. I plopped in another set of eyedrops and headed home for a couple of hours before I’d be back for the post-op appointment, which went not unlike the one for the left eye. Another week of 3 drops, 3 times a day in the right eye until we were back for the second follow up appointment. We could stop the drops for the left eye, which felt like a small victory.

At the second follow up, the doctor noticed some swelling in the left (first) eye, so my small victory evaporated as the regimen was shifted again: 2 drops, twice a day, in *each* eye until the final follow up appointment at the end of April. As I’m typing this, we’re counting down the last few days before what should be the final follow-up appointment, the much-anticipated measurements for her final eyeglasses prescription, and The End of the Eyedrop Episodes. There’s a part of me that will rejoice, and another part of me that’s already working on a reason to go over there every day anyway. Maybe just not twice a day. . .

Parenting the Parents – Part XI. The Cataract Chronicles.

If you have aging people in your life, at least one has probably had cataract surgery. I think I might even know a few people who’ve had this often life-altering procedure who don’t fall into the “aging” category. In either case, you may have heard about the procedure, and the preparation and follow up care that is required. For people without cognitive impairment (or unsteady hands, or eye/ eyedrop phobias), I’m certain the whole thing barely rises above a minor inconvenience, especially considering the abundant payoff.

With mom’s particular brand of dementia, no appointment or procedure can be taken lightly. Leading up to even routine doctors’ appointments, she scrutinizes the weather forecast for a week in advance; lays out her clothes the night before; and asks me at least twice in the two days ahead of time what time we’re going to leave. When you’re talking surgery, especially not long after having had an unscheduled pacemaker implantation, the unknowns gather themselves into a category 5 hurricane of anxiety. The eyedrops; the preparation for the surgery and the surgery itself; the immediate post-surgical follow up; the eyedrops; the ongoing follow up appointments; the eyedrops. . . none of it can really just happen “in the flow.”

The surgeries were going to take place a month apart: left eye at the end of February; right eye at the end of March. They would be performed at an eye surgery center about 15 miles away, where our ophthalmology group, and apparently several others, perform various procedures all day, every week day. (At the second visit, my curiosity piqued by the volume of patients who moved through the waiting room in the time between our arrival and post-operative departure, I asked how many surgeries they perform in a typical day there. I was astounded to learn that it was between 40 and 60).

Before the first surgery we needed a pre-operative physical, which had to be completed within a week of the first surgical date. Mom kept getting confused about the timing of that appointment and worrying that we hadn’t scheduled it at the right time. Once it was clear the timing was OK, the worry shifted to whether there would be something wrong that would prevent her from having the surgery, or if her pacemaker would present an obstacle. Could they do cataract surgery so soon after she’d had a pacemaker? (It would be 7 weeks post-pacemaker by the time her first eye was on the docket). I assured her that doctors perform cataract surgery on people with pacemakers all the time. I’m not entirely sure her anxiety allowed her the luxury of believing me.

So yes, complicating this was also the fact that we were still in the wake of post-pacemaker implant follow up appointments, and while I was keeping it all organized, it was thoroughly overwhelming her. It didn’t help that the hospital’s cardiology group, not realizing mom now had her own cardiologist, had scheduled a series of follow ups before mom was even discharged from the hospital that were then also scheduled separately by her cardiologist. It took me a couple of rounds of appointment change and reminder calls from the hospital’s group to figure out that these were duplicate activities and that I could cancel the ones with the hospital’s group, but with the calls coming in to my parents’ phone rather than mine, poor mom was completely confused. I think I’ve now informed all her doctors that appointment reminder calls should come to me. If you are in the world of caregiving for someone with dementia and haven’t yet managed to get yourself on the HIPAA privacy releases at their doctors’ offices and those reminder calls switched over to you, my advice is to try to get that in place sooner than later. It’s a sanity-saver. For everyone.

A week prior to the first surgery, mom was supposed to stop taking one of her over-the-counter supplements because of a potential complication that could arise with it. The surgical center had apparently informed her of this when they called her to tell her what time to plan to arrive on the day of the surgery, but somehow that directive escaped her. I discovered it when I saw that she’d written some notes down about an arrival time and the address of the center on a random slip of paper, so called them myself to confirm what she’d written. They mentioned the over-the-counter medication to me. It was now 5 days pre-op, and I asked if that would pose a problem. They said it wouldn’t.

She was supposed to fast from midnight the night before each procedure. She had written it in her calendar, and I reminded her when I left after administering her last round of eyedrops the previous evening. For good measure, though, I arrived early enough on the day of each surgery to intervene as she woke up, just in case.

As for those confounded eyedrops, most unimpaired people likely don’t give them a second thought. If we lived under the same roof, I might not have either, but I don’t. Even though I’m only 3 minutes away, the “Eyedrop Episodes” were folded into the overall outline of my days. For each eye, we began a regimen 3 days in advance of the surgery: 3 different drops, at least 5 minutes apart, 3 times a day. Each morning I’d motor down the hill, typically sometime between 9 – 10 a.m., to administer the first dose. Then, between 1:00 and 2:00 came the second dose, with the third usually falling between 5:30 and 7:00. We were supposed to administer at least the morning drops the day of the surgery; because the first surgery wasn’t scheduled until mid-afternoon, I did two rounds. I figured more would follow after the surgery.

The pre-op instructions from the doctor suggested that the patient have someone stay with them the night of the surgery in case of any complications, so that morning I packed my things. I included my muck boots, because light snow was forecasted for that afternoon and overnight, another factor stressing mom out, and, if I’m being totally honest, me too – even light snow falling at the wrong time of the day could sometimes spell a 2 hour odyssey for what should normally take 35 minutes or less, and we’d be getting out of there right in the thick of rush hour. I didn’t really relish the thought of being stuck in traffic in the snow on the way home from surgery, so with an abundance of caution, I left all my overnight stuff in the back of my car. Worst case we’d stop at a hotel. Gratefully, the weather gods smiled and the snow had no impact.

The next morning she was supposed to remove her eye patch & dressings, and I was to give her another set of eyedrops before we went to the doctor for the post-op follow up visit. She wasn’t allowed to bend over (i.e. let her head drop below the level of her waist) for at least a week, which might alter some aspects of how she helped my dad when their caregiver Hannah wasn’t around (helping him with his socks and shoes, or the assists I knew she sometimes provided when he was changing a Depends). All of this made the next morning somewhat eventful for me as I tended to both of them before Hannah arrived. We saw the doctor and all appeared well; he instructed us to continue with the 3 drops a day regimen until the next appointment, a week away. On the way home I asked mom if she wanted to go out for breakfast – an unexpected treat.

Back at home that day with Hannah, the two of them came up with some revisions in how she helped dad with his footwear (and Depends) so they could manage safely on their own: mom would sit on the fold-down seat of dad’s walker and he’d lift a foot (or both feet, one at a time, in the case of a Depends) high enough for her to grab it and guide it to the edge of the seat where, from her sitting position, she could help him with socks, slippers and shoes. With the Depends, as long as she could help him get them to knee level, he could deal with the rest on his own.

At the follow up appointment a week later, I expected to be done with the drops until the next surgery, but alas, that was not in the cards. The nurse said it casually, at the very end of the appointment, after the doctor had left the room: “So you’re going to continue the drops,” thinking she was confirming something the doctor had said, but he hadn’t. The exasperation lurched out of me before I had the wherewithal to stop it: “Really?? All of them?!? 3 times a day?!?” I felt the same burning frustration I did when I used to do the Jane Fonda workout back in the late 80s and she’d pretend the excruciating set of donkey kicks was ending as my glutes were bursting into flames: “5 more! 4! 3! 2! 1! Annnd another 5!” One of the drops was eliminated, and the frequency dropped to 2 times per day, but the Eyedrop Episodes were to be a part of my life for at least another 4+ weeks – after the second surgery.

The twice-a-day routine settled itself into my life. Once or twice I had James, my 22-year-old, pinch hit. This worked once and failed once, when we’d pre-planned that he’d head over between 6 and 7 p.m. because I would be out at a dinner engagement. I arrived home at 8:30 to discover that he had completely forgotten (calendar reminders, anyone??). I yelled at him for lapsing in the one responsibility I’d asked of him that day and Tim threatened that he’d better get down there and do it. Because I hadn’t even left the threshold yet, as he emerged from his room to head down the stairs, I snarled passive-aggressively that I’d just do it myself. This was getting to me, but this was my reality, so I vowed on my drive down the hill to just suck it up and deal with it. With a smile. I needed to remind myself of the advice I gave out all the time: the secret is all in the attitude. The more I fought it, the crankier it made me. Yes, there was still another eye to go. So be it.

Parenting the Parents – Part X. How do you Solve a Problem Like Dementia?

If you’re of a certain age, perhaps the title of this week’s blog puts a certain song from “The Sound of Music” in your head. Sorry if that now becomes your earworm du-jour.

Going back a few weeks, I shared how mom’s post-surgical home-care occupational therapist performed a cognitive screen with her and her scores indicated fairly significant dementia. I wasn’t there when the O.T. (I’ll call her Nina) did the screen, but knowing how my mom had been struggling emotionally with all the challenges aging suddenly seemed to be throwing her way, I worried that she’d internalize this, adding it to her growing list of worries, fears, and perceived shortcomings. (Among them: her need for a pacemaker; a recent visit to the eye doctor that resulted in her being scheduled for upcoming cataract surgery on each eye, along with 3 separate follow-up appointments for each surgery; her ongoing bouts of word-loss – being able to picture something but not give it voice). No amount of reassurance or logic seemed to change the self-critical frame into which she painted these facts.

I asked Nina how mom had reacted. She told me she (mom) knew she “hadn’t done well,” but Nina reassured her that there was no “well or not-well,” and that it had nothing to do with her intelligence. I knew my mom. I knew she’d hear the words; but I also knew they’d likely bounce uselessly off her looming sense of diminishment. I pressed, “how did she feel about *that?*”

“Well, she wasn’t too happy, but I talked to her about it and by the time I left she seemed better.”

Nina suggested that I get mom in to see the geriatric psychiatrist my dad had been seeing (“Dr. M”). I promised I would, and wondered out loud how on earth I was going to bring this up with her. Nina reassured me that I shouldn’t feel like I had to do that right away, and that when I did, I didn’t have to make a big deal about it. The reality was that it was important that we get it checked out because we might be able to do something to improve it. My dad did seem to be doing fairly well on the medication he’d been taking, but mom’s “presentation” was so different that I was skeptical the same thing could work for her.

I called Dr. M’s office to see if I could schedule an appointment around the same time my dad was slated to go back for another follow up in late March (it was early February). Though the practice wasn’t taking new patients, they were accommodating considering that dad was already a patient, and even maneuvered things to schedule mom’s appointment in the time slot immediately prior to dad’s. They asked if we’d had any MRIs or CT scans and I shared with them her fainting episodes prior to her pacemaker implantation, and that 2 CT scans were done prior to her surgery. They said they’d arrange to get the images from her doctor. I was happy for all of it, but inside I was still fretting about how to tell her.

I called my sister and filled her in. She had no difficulty relating to my concern about bringing it up, so we agreed that I’d bide my time and wait for the right moment to “go there.” Several days later, I decided to write the appointment onto their two calendars, in plain sight, as a possible catalyst. It was scheduled for a Friday afternoon – as it happened, the Friday before the Monday she was scheduled for her second cataract surgery, so I figured she’d be checking the calendar as the date of the cataract surgery approached. I wanted to let it come up in the natural flow of things. Eventually, it did, two days beforehand.

Mom: “Hey, how come I have an appointment on Friday with Dr. M, too?”

Me: “Remember your occupational therapist Nina? And that test she gave you?”

“No. . . not really.”

“That’s OK. Anyway, she shared the results of that test with Dr. K, and Dr. K recommended that we get you in to see Dr. M, too. You might not remember because of everything else that was going on, but in one of our follow up appointments with Dr. K, she recommended that we have you see Dr. M.”

“Oh. Okay.”

When I headed home a little while later, I wondered if that was it – all that worrying over nothing. The next day (the day before the appointment), she revisited it: “I remembered that test Nina gave me. So what’s going to happen on Friday?” Her voice was slipping back and forth over the fine lines between curiosity, fear, and irritation.

“Well, you know how you’ve been getting frustrated over losing words sometimes? Seeing Dr. M will help us start to figure out what’s going on with that. You’ve noticed how daddy’s been doing pretty well on his medication from Dr. M, right? They may be able to do something that will help you, too, but they need to see you in order to do that.”

Once again I was relieved that she seemed to accept this explanation with little angst.

When I arrived Friday prior to the appointment, however, the angst level had clearly ticked upwards, evidenced with mom’s defiant announcement: “I don’t know what they’re going to ask me today but I may not be very nice about it. They might just kick me out.”

“I don’t think they’ll do that mom. Remember, this is exactly their specialty. They’re here to help figure out what’s going on, and to come up with things that might make it better.”

As we pulled into the parking lot of Dr. M’s office, she declared, “I just want you to know I’m not very happy about this.”

“I know you aren’t, but we trust Dr. K, and she wanted to make sure we did this.” It was helpful to fall back on Dr. K, for whom mom had developed great affection – she recognized that Dr. K’s actions the day of the pacemaker implant had probably saved her life.

The first 30 – 40 minutes of the appointment were tough. Karen, the therapist, administered another SLUMS test. In many of the areas, mom did fine, but it was hard to watch her struggle with others – not for the fact of any cognitive deficit on its face, but for how hard it was for her to wrestle with the emotions that came up when she had a tough time with something. Karen was patient and careful, reminding mom that there really were no right or wrong answers. When mom would struggle she’d sometimes prompt gently, following, I’m sure, administration protocol for the test, as eventually, it seems that scoring weighs out the differences in how questions are answered (straight away; with prompting; or not at all). She also went through a series of depression-related questions. We talked about mom’s hearing, which had also been problematic.

Ultimately, Karen walked us gently back through the results of the SLUMS test and depression screen. She shared that there were some areas where mom’s scores indicated normal cognitive function, and others where there were challenges. She also highlighted that mom’s score on the depression screen fell just below the threshold for clinical depression. She assured mom that this was not at all unusual, and that depression could be a significant factor in cognitive functioning. Very often, she noted, treating the depression made a big overall impact.

We talked. I reinforced how glad I was that we were there and how it hurt me to see mom beating herself up when she couldn’t remember things or when words wouldn’t come out. I confessed that it seemed to me that she felt it meant that she was somehow “less than,” or not smart, and how untrue that was. We cried. We hugged. The whole mood shifted – so much lighter. Karen reiterated the importance (as she’d done in the past with dad) of physical exercise and doing new things to stretch the brain. We made a list of things we might be able to do: playing set-back and re-learning cribbage. Making bird houses. Getting some new CDs to listen to. Dr. M came in and, as he reviewed the scores (and likely Karen’s notes), he echoed Karen, stating that he’d like to take a shot at treating the depression first, to see how that might go. Mom was on board.

Dad arrived for his appointment right on time thanks to Hannah, their caregiver. I brought him in to mom’s appointment, as had been the plan, and we brought him up to speed with the findings and the plan for her. Dad was his characteristic, agreeable, low-key self. We rolled from mom’s appointment into his, which was a basic check-in. It went smoothly. We made follow up appointments for both of them.

While Hannah took dad home, I took mom, stopping on the way home for some groceries. She told me, more than once, how much better she felt, and how good it was to get all of those feelings out. I told her how glad I was, and how optimistic I felt that we were on a more positive path.

I walked away enlightened about depression and its link to dementia. Everyone’s is probably slightly (or a lot) different, and determining other areas of potential impact (such as depression) is important to coming up with a plan to manage it with the most appropriate approach. Now to get them to exercise, and to their proverbial, Sound of Music Switzerland. . .

Parenting the Parents – Part IX. A New Normal.

I thought I was going to write more this week about my mom and her ongoing diagnosis. But, life. More specifically, life when your parents’ well-being becomes your responsibility.

It’s Masters Sunday. Nearly a religious holiday in my house. Due to impending storms in Atlanta, they moved the whole final round to earlier in the day, and coverage was set to start at 9 a.m. I’m taking care of our niece’s 3 beautiful cats this weekend while she’s away, so I headed over there early (yesterday, and today), to be sure I gave the effort its due, but (today) could still watch the tournament relatively unimpeded.

I really like getting up as early on the weekend as I do during the week. Like 6 a.m. early. Mornings are my happy time. Getting up early and doing what I really need to do makes me feel accomplished. It’s also my peaceful time, before any shit has escaped to hit the fan. Plus, Tiger said at the end of play yesterday that he’d be getting up at 3:45 this morning. Who was I to sleep late?

Yesterday morning on my way back from my niece’s, my mom called my cell. Nothing to panic over, just asking me if I could pick a few things up at the store. It just so happened that I was 2 minutes away from our little market down the hill and the timing was perfect. On the way back this morning, my husband popped up on the caller ID as I neared my exit on the highway:

“Your mom just called. She sounds pretty upset. She says your dad has a fever and his cough is back and she’s kinda freaking out.”

“Okay.” (I should tell you: though I was hoping this would be a tiny, non-event-blip on the ever-spinning radar that is now life, that I took dad this past Monday for a follow up x-ray from his December/January bout with pneumonia. The doctor called a couple of days later to say that there was still a small “infiltrate” at the bottom of his left lung, so she was prescribing him some antibiotics. All this started twisting wildly in my head. How could he be getting worse when he was on day 4 of a 5-day antibiotic zap?)

“She asked if you could bring our thermometer. I told her I’d call you and have you come here first and then go there.” (They have a thermometer, but we haven’t been able to find it since their move. I decided to stop at the CVS on the way home to just get them a new one. That would be faster than going home then doubling back to their place, and they’d have their own once again).

I felt my adrenaline surge and my pulse rate increase as I hung up. I tried to breathe and settle myself down, but by the time I was sitting at the traffic light at the end of the exit right before the CVS, my brain was sprinting down a too-familiar track: what if this was it? Another fever with just a small pneumonia infiltrate. . . that didn’t make sense. Another round of sepsis? What was going on? Would I drive him to the E.R? Would I have Tim take my mom or try to keep her calm at home this time? What if this was it??

I got there. He was perched unsteadily on the side of the bed. He said he felt weak. I asked if he’d eaten anything. He hadn’t. I felt his forehead. He didn’t feel too warm. Kinda normal, actually. I cleaned the thermometer with alcohol (I’d broken it out of the package in the CVS parking lot and tested it on myself to be sure it was working – it was one of the digital kind with an 8-second read. If he was feverish and shaky, I didn’t want him trying to keep an old-fashioned mercury one under his tongue for as long as those take, but I also didn’t want to get it there and find the battery was dead or that it was a lemon). I took his temperature. 98.9. Normal. I took it again to be sure. 98.7. Phew.

I peeled a clementine for him to get his blood sugar up. He ate it. I asked if he wanted some fried baloney (his favorite – for real). He shook his head; meh – not really. That registered. Something was off. Mom asked if maybe he’d like some soup. It wasn’t 9:00 a.m., but who cared? He said yes. We got him some juice and ice water while I heated up the soup and did mom’s post-cataract-surgery eye drops. When the soup was almost ready, I supported him as he moved over to “the chair” and got him settled in. I made sure he took all his meds. I asked him if the cough felt like it was from a tickle in his throat or if it was in his chest. He said it felt like his throat, so I suggested to them that it could possibly be the increasing pollen in the air that was bothering him. What did I know, but I wanted to quell any panic that might be lingering around the frayed edges of the morning.

Before I left, I made sure he ate all his soup. He drank a juice box and had some ice water and took his meds. I promised to pick up more fruit before I came back for mom’s afternoon eyedrops, and told mom to call me if they needed anything or if anything changed with dad, then headed home to watch the Masters. When the phone rang a couple of hours later and I saw it was them, my heart jumped in my throat. I was relieved when it was only a request to pick up more bread, too, and an apology for being such a pest.

“No problem, mom. Really. You’re not being a pest. It’s no problem. I love you.”

Just a Quick Post for those following Mom & Dad Monday

“Love to Move”Hey everyone! I just posted this on the Mom & Dad Monday Resources page, but I recently discovered this wonderful program of chair exercises you can share (and do!) with your loved one(s). I showed these to my mom this morning (while attempting a couple of them myself – that was eye-opening . . .) – we had a ball and were laughing like crazy as we tried them. They are as much for stimulating the brain as for encouraging movement. These will definitely become part of our repertoire!! “Love to Move”